Bracketing is an underutilized technique counsel can apply when negotiating settlements in mediation. Counsel must understand what bracketing is, the mechanics of how it operates, the significance of the midpoint, and why it works. When used effectively, bracketing can bridge significant offer and demand gaps between parties and achieve settlement. In this article, Hon. F. Keith Brown, (Ret.), senior mediator and arbitrator at ADR Systems, contributes his insights to help define the intricacies of bracketing for attorneys.

Bracketing in Mediation

Bracketing is a negotiation strategy in which a party proposes a range — rather than a fixed figure — for potential settlement. This range helps define the Zone of Possible Agreement (ZOPA) and invites the other side to engage in a more flexible, collaborative dialogue. It’s not demand and it’s not an offer. It’s a tool designed to break through impasse and reinvigorate stalled negotiations.

When counsel introduces a bracket, it often signals a willingness to compromise and a shift away from rigid positional bargaining. Bracketing reframes the negotiation by focusing on ranges that may contain shared interests. This can generate momentum, especially in mediations where parties have become entrenched or fatigued by incremental back-and-forth.

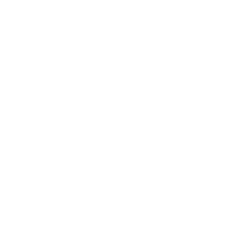

Consider this: Plaintiff demands $11 million, and defendant offers $1 million. The $10 million gap is vast, and negotiation could take hours of slow movement. Instead, plaintiff might propose a bracket of $8 million to $10 million, while defendant counters with $2 million to $4 million. Though still far apart, the parties have now narrowed the field. If they eventually agree to a bracket of $5 million to $7 million, they’ve created a shared framework for meaningful negotiation. This shifts the conversation from positional defense to problem-solving — making resolution not just possible, but probable.

Understanding the Midpoint

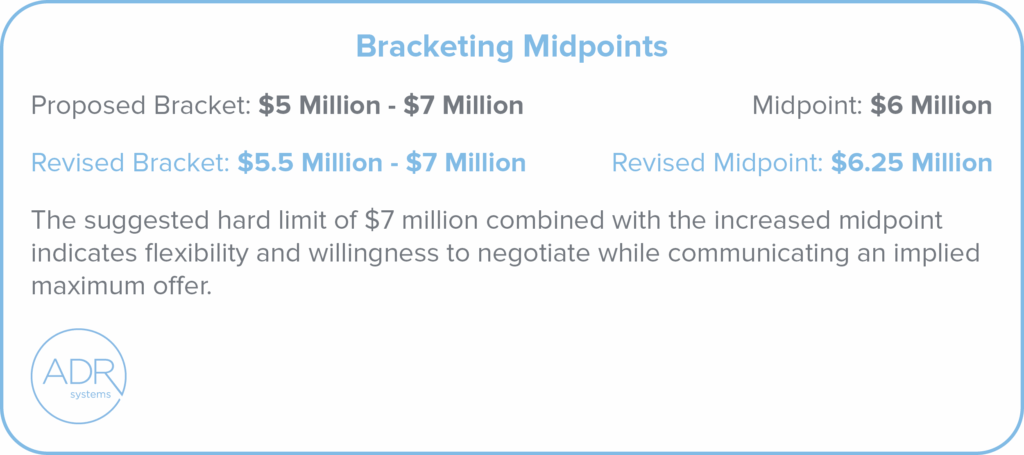

The effectiveness of bracketing hinges on one critical element: clarity around the meaning of the midpoint. The midpoint of a bracket — say, $6 million in a $5 million to $7 million range — is often interpreted as a signal. It may suggest that the proposing party is willing to offer or accept that amount contingent on the other side’s agreement. But this assumption can be misleading.

In some cases, the midpoint is merely a mathematical center, not a settlement signal. It may reflect a range for discussion, not a bottom line. If a party proposes a bracket but does not intend to settle at or near the midpoint, it is essential that they communicate this clearly. Otherwise, the bracket may be misread as a soft offer, leading to false expectations. For instance, if defendant proposes a $5 million to $7 million bracket but has authority only up to $5.5 million, failing to clarify this could result in the plaintiff assuming $6 million is on the table — when it’s not.

While the midpoint often becomes the psychological anchor, it’s not the only data point that matters. The width of the bracket, the direction of movement, and the timing of the proposal all convey information. But without transparency around the midpoint’s intent, the bracket risks becoming a source of confusion rather than clarity.

Why Bracketing Works

Bracketing is a useful tool in negotiation because it mitigates psychological principles that, left unchecked, can halt a settlement. Specifically, it limits the effect of anchoring bias and cognitive narrowing.

Anchoring bias occurs when the first offer in negotiation disproportionately influences how subsequent offers are perceived. This initial figure can distort expectations, skew assessments of fairness, and shape the trajectory of settlement discussions. Despite being a well-documented cognitive bias, anchoring continues to exert subconscious pressure, often narrowing the field of acceptable outcomes.

Bracketing counteracts this effect. By shifting the conversation from fixed numbers to negotiated ranges, it reframes how parties interpret value and movement.

Cognitive narrowing refers to a psychological phenomenon in which an individual’s attention and reasoning become restricted, often under stress or emotional strain. As the mind narrows its focus, it becomes harder to consider alternative perspectives, broader implications, or creative solutions. This can be particularly problematic in negotiation or mediation, where openness to multiple viewpoints is essential.

Bracketing serves as a strategic counterbalance to this tendency by introducing a structured range within which parties can negotiate and expand the perceptual field. As the brackets tighten, the process subtly shifts attention from entrenched demands to areas of overlap. This reframing reduces the psychological discomfort associated with making absolute concessions, allowing parties to engage more constructively.

Eventually, the Zone of Possible Agreement (ZOPA) becomes clearer and more acceptable than the original positions. What once felt like a compromise now appears as a shared solution. The narrowing of brackets broadens the parties’ sense of mutual flexibility, reinforcing common ground and increasing the likelihood of resolution.

Bracketing has gained popularity because it helps parties get to the heart of why they are in mediation: to arrive at a number and settle the case.

Bracketing: A Snapshot

Bracketing is more than a tactical maneuver — it’s a dynamic negotiation strategy that fosters collaboration, builds trust, and facilitates settlement. When used effectively, bracketing empowers both mediators and parties to shift from positional bargaining toward mutual problem-solving, transforming conflict into consensus.

Lawyers who understand how to propose, interpret, and respond to brackets are better equipped to negotiate a settlement. In complex cases, especially those involving layered liability or sensitive damages, bracketing becomes a tool not just of strategy, but of structure — helping parties see the path forward when it seems unclear.

…………

Hon. F. Keith Brown, (Ret.) has extensive experience in settling personal injury, workers’ compensation and commercial matters. As a mediator, he is known for his keen ability to easily connect with people and promote productive communications between all parties. Judge Brown is a beloved pillar of the community, who has been recognized numerous times for community service.

Request Judge Brown’s Availability

ADR Systems, It’s Settled.®

This article was originally published at the Chicago Daily Law Bulletin. The edited version can be read here.